Crowdfunding for Climate Change

Jack Pead | August 27, 2014.

Even though climate change negotiations often proceed at a glacial pace, there are strong reasons to anticipate a legally binding global treaty in Paris in December 2015. Individuals may be able to put their money behind the message, if the United Nations allows crowdfunding for the new Green Climate Fund. It would be the first time the UN allows individuals to be directly involved in funding climate change mitigation and adaptation projects in developing countries.

Crowdfunding has great potential to overcome the most intractable problem that faces the negotiations: the so-called Prisoners’ Dilemma.

A Prisoners’ Dilemma is a game where each individual player always has an incentive to betray the other players in the game. Climate change negotiations are viewed by some in the same way: if your negotiating partner is secretly emitting pollution, you might as well do it yourself.

In this case, the players are the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, or UNFCCC. This international game plays out every year at the Conference of the Parties, known as COP. The COP is where countries are supposed to show their cards and state what actions they will take to help mitigate dangerous climate change. In recent years this game has been like watching children play cricket: mildly amusing, but exceedingly frustrating.

The infamous Copenhagen conference was the pinnacle of mediocrity.

After much anticipation, the only outcome was a vague accord agreed to by just five countries, known somewhat euphemistically as the Copenhagen Accord.

Once we accept the idea that for a country to mitigate emissions, there will be, at least in the short-term, some negative impact on economic output (an idea which only the most technophilic environmentalists still refute), it follows that for any country at the COP, from the largest emitter to the smallest, the best short-term outcome is to have every other country do a lot to mitigate climate change, and for them themselves to do relatively little.

This is because they receive the benefits of other countries reducing carbon emissions while not having to take mitigation actions themselves. It’s like a lazy housemate not helping to clean up after a party.

Regardless of what they expect other countries to do, we would expect each Party to the treaty to ultimately come out with relatively weak mitigation actions at each COP. This is what we have seen.

However, there is reason to believe that in recent years, the process has changed for the better. Since the 2011 conference in Durban, Parties have been working towards reaching a binding agreement in 2015 that will begin in 2020.

This might not sound like a lot, but by changing the process from a series of individual meetings to an iterative process where Parties must gradually make commitments over a period of time leading up to the 2015 end goal, the outcome may be quite different. At least this is what the Game Theory would suggest.

It’s also known as iterative negotiating. Countries involved in such a process, especially major emitters, cannot expect others to make material commitments if they do not make their own.

The timeline of the negotiations also gives Parties time to assess what commitments they are capable of making given political constraints within their countries. In this context, major emitters such as the USA and China have recently made important announcements regarding emissions mitigation actions. Such announcements put these countries on a path towards making binding commitments and signal to other Parties to also make increasingly firm commitments in the lead up to the COP in Paris in 2015, where the new agreement will be negotiated.

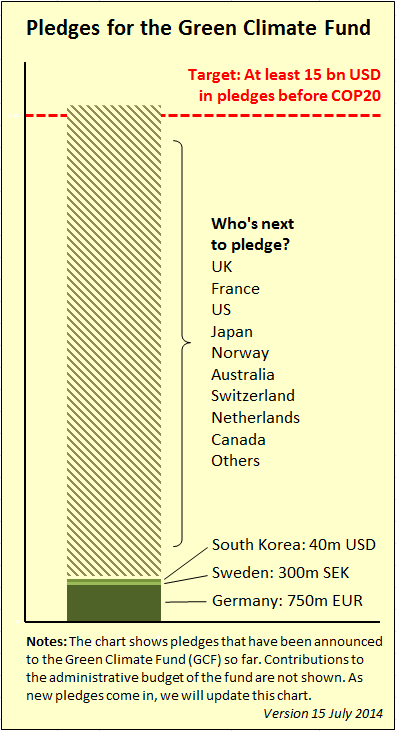

Graph: Jan Kowalzig, Oxfam

The Green Climate Fund

In May 2014, the UNFCCC mobilised a global Green Climate Fund, a break from the historical approach of focusing on emissions mitigation. While various multilateral green funds already exist, the GCF is intended to act as the key centralised global fund for green initiatives, leading to more effective funding collection, project selection and delivery. With funding from UNFCCC Parties, the GCF will finance climate change mitigation and adaptation projects in developing countries. Project selection will be based on consensus decision-making by the GCF’s 24-member board, which is made up of equal numbers from developed and developing countries.

Over the course of 2014, the GCF board has been surprisingly quick in becoming operational.

But while the GCF is now ready for funding contributions, its ability to operate efficiently and effectively will not be tested until it is capitalised, a process which is expected to occur in the last quarter of 2014, at the UN Secretary General’s Climate Summit in New York in September and at the COP in December.

A key question for the GCF is how its board will objectively allocate funding to projects when such a diverse range of potential mitigation and adaptation projects will be competing for funds. While robust methodologies for project assessment have been developed over the past two decades, the variety of potential projects is so diverse that comparing projects is almost always impossible.

As an illustration of this challenge, under the Clean Development Mechanism, a program of the Kyoto Protocol, there were 89 approved large-scale project assessment methodologies.

Despite its novel status, the biggest problem for the GCF could be that the process of its capitalisation is at the mercy of the same kind of Prisoners’ Dilemma that has stymied UNFCCC emissions mitigation negotiations. Each Party will happily let other countries shoulder most of the cost if they can get away with it. This dynamic threatens to stall the capitalisation process of the GCF. Hela Cheikhrouhou, the GCF’s executive director, recently outlined a US$15 billion target for contributions by the end of 2015. While some countries have already shown their faith in the fund (Germany in June announced a multi-year contribution of €750m), other countries, in particular less-developed countries, are showing signs of sitting out at least the initial round of contributions.

Crowdfunding

One promising option being considered is to open up contributions to the public through crowdfunding. This would allow anyone to quickly and easily donate to the GCF online. Currently only countries are able to contribute to the GCF, but the Board has kept the option of adding other funding channels open: this may include crowdfunding.

Crowdfunding has been around for less than a decade and is still in its infancy. Most examples of crowdfunding have been discrete projects that project founders are looking to finance in order to bring them from the concept stage through to fruition. It has been hugely popularised with platforms such as Kickstarter.

Funding can be done on a donation or equity basis. In the equity form, crowdfunders get ownership over some share of the project, commensurate to the size of their investment. Donation based models offer the donor the ability to support the project but not receive any economic ownership. There are divergent views on whether the GCF should look to utilise equity or donation based crowdfunding.

Proponents of equity based funding say that its use as a source of funds for the GCF would open up a huge pool of potential investors, due to the large and growing amount of green investment capital globally. However, detractors of the donation-based approach point out that even green investors may not view crowdfunding for the GCF as an acceptable form of investment. Historically, green investment capital has focused on not investing in dirty energy projects, like coal and gas, but still achieving competitive rates of return. GCF projects would most likely achieve lower investment returns for the sake of emissions reductions, something that would be unacceptable to most green investors. Given the track record of green securities (EUAs, CERs, etc.) associated with mitigation projects and the volatility of associated carbon markets, there would exist little palate for such investments.

This leaves the donation-based approach to crowdfunding. While it may not open up the GCF to the large pool of green investment capital, it would empower individuals to be directly involved in funding climate change mitigation and adaptation projects in developing countries. Donors would contribute to the fund as a whole, with the GCF Board ultimately deciding which projects are funded. It is unknown how much people may be willing to give, but by bypassing environmental organisations where individuals concerned about climate change have historically channelled their donations, directly crowdfunding the GCF would decouple the issue of climate change from general environmentalism and would likely open up a new pool of potential donors. Seeing as crowdfunder donors would likely approach contributing from a more altruistic perspective than countries, they are not subject to the Prisoners’ Dilemma facing countries.

If individuals are given the opportunity to directly finance climate change mitigation, and be recognised for it, a significant amount of capital may be raised through this channel. With UN support, there is no reason why this project could not far surpass previous examples of crowdfunding in terms of the amount raised.

Yet, there are still concerns around the concept .

Some civil society groups and developing countries have pointed out that by allowing crowdfunding as a source of capital for the GCF, it may take the onus off major emitters to capitalise the fund. The concept of equity is central to climate change negotiations. Equity in this sense means that countries that have been major emitters historically should shoulder an appropriate amount of the burden of reducing emissions. Another question is whether crowdfunding has implications for the role of governments in dealing with global issues in modern society.

As it offers an incremental source of funds, there is little reason for the GCF board not to push for crowdfunding to be added as a source of capital for the GCF.

To make the crowdfunding concept a success, the GCF board would need to work to show that funds contributed will be used effectively. An agreement to make donations tax deductible will also go a long way to gaining support, particularly from large private philanthropists.

Crowdfunding, although unlikely to become a major source of capital for the Green Climate Fund, is a potential gold mine in the fight to finance climate change. It would make individual people financial stakeholders in the future of the planet.

comment