As Friday’s sun rose over the vast Pacific ocean to light up the Western shores of Lima, a new report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) put the state of the ongoing international climate negotiations in a new light.

According to the UNEP report, even if we are able to keep global warming below the agreed upon 2ºC threshold, the world will need US$150 billion annually by 2025 and as much as $500 billion by 2050 to finance the adaptation needed to cope with a dramatically changed world.

Countries have pledged approximately $10 billion in public funds for both finance and adaptation, with a commitment to ramp up to at least $100 billion dollars by 2020. With little progress being made on a separate adaptation mechanism, and adaptation unlikely to be supported significantly by private funds, it is unclear where additional funding will come from to close the gap and cope with things like higher seas and more severe storms.

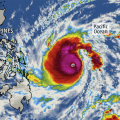

Looming over all of this, another typhoon—Typhoon Hagupit—is making landfall in the Philippines. This would be the third year in a row that a much deadlier than average typhoon made landfall in the Philippines during the the annual climate negotiations. Typhoon Haiyan provided for a stark and tragic reminder of the impact of higher seas, warmer waters, and a warmer atmosphere last year, and Habigut is likely to stimulate similar reactions.

The unfortunate situation in the Philippines also serves as yet another reminder that there is a need for loss and damage. A mechanism that compensates and rebuilds from climate disasters that affect the worlds poorest countries is essential if the countries are to uphold the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities.

In good news, particularly in the lead up to Paris, progress is being made on securing a five-year review and commitment cycle for Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) from 2020 on. Civil society have been strong proponents of a shorter commitment period as it has more potential to result in increasing ambition and adequacy over time.

The Marshall Islands has submitted this language into the draft text for the Ah-Hoc Working Group for the Durban Platform, ADP, and is being supported by other important countries and groups. The EU so far remains steadfast in their insistence on a 10-year period; hopefully they do not block this flow of progress.

Just as the oceans connect far and foreign shores, so too are we all connected by our common humanity. Demonstrators inside the conference made a powerful statement, yesterday morning, that a crime against an individual is a crime against all of us too. Participants took part in a solidarity action with the widows of four Saweto tribal leaders who were murdered in their battle against illegal loggers in the Amazon forest bordering Peru and Brazil.

The Saweto people have long been lobbying the Peruvian government for land sovereignty. Indigenous land sovereignty and deforestation in the Amazon are two issues that are being fiercely lobbied and negotiated at this year’s conference in relation to the REDD mechanism.

While negotiations went late into a night illuminated by the pull of a full moon, the Peruvian government hosted a side event on the importance of oceans and their fragility. In the release of a book seeking to raise awareness around this, Peruvian Environment Minister and COP President Manuel Pulgar-Vidal stated: “The ocean is the source of life. We must promote the value of the ocean. We must celebrate the ocean.”

As negotiations progress in Lima, unprecedented ocean acidification, eroding shorelines, crippling floods, and deadly storms will become the new norm if this fortnight doesn’t put us on a the pathway to an ambitious global agreement in Paris. We doubt that there will be much celebrating then.

comment