Negotiation Compass

Hamish M | December 2, 2015.

Negotiations for a new global climate agreement are now in full swing in Paris. Talks began on Monday with world leaders outlining their visions to inject political momentum into the process. There is an air of cautious optimism for the two weeks ahead.

The negotiators have been told to produce a full draft of the new agreement by midday Saturday. That leaves a window of just three more days for the most complex and politically fraught piece of international legislation in history to come together.

The text is currently over fifty pages long, and there remain around a thousand interlinked points of contention that need resolution. In its final form, the agreement is likely to be one-tenth its current size, and needs to gain the consensus of all 192 countries. What lies ahead is no small task, but one that they have been working towards for many decades.

Nor is it a simple one. Climate negotiations take place in the deeply inaccessible language of international diplomacy. To help demystify the negotiations, The Verb has produced a Negotiation Compass. As the negotiations unfold, we will use the Compass to translate diplomacy-speak and double entendres into plain language, outline possible scenarios we might end up with, and to explain the power plays behind it all.

We will post daily state of play updates using the compass to assess the state of the negotiations. And since the agreement hinges on minute word choices, we have created a deep-dive into what language to look out for in each scenario. This will be a handy cheat sheet as we move towards the final agreement.

1) Talks Gridlocked Over Money, 3 December

2) As Talks Stall, The Iceberg is Ahead, 4 December

3) Back From The Brink, 8 December

Success in Paris depends on ambition and architecture

The Paris agreement will ideally not be a one-off agreement that needs replacing in another decade like the Kyoto Protocol. The president of the conference, French environment minister Laurent Fabius, told observers today that: “Paris should be something permanent. Something not to be reinvented each time”.

To be successful, it needs to articulate bold ambition on climate action, and it needs to set up the right institutional architecture to achieve that ambition. It should herald the formation of a new international climate regime that is both enduring and dynamic that can bring together nations to act on climate change immediately. It should also facilitate increasing action on climate change that needs to be pursued going forward to meet the stated goal of staying below 2°C of warming.

There are seven key issues that will form part of the agreement

This agreement is about halting climate change. But within that broad aim, there are seven key issues that countries need to agree on. We will need strong ambition and architecture across each for the agreement to be a success.

1. Short-term mitigation

This is about commitment to cut carbon emissions before 2030. The period before 2020 is covered by the Kyoto Protocol, and the 2020-2030 period is covered by recent commitments known as Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs). The big question is whether the Paris agreement will legally bind countries to meet their INDCs in order to accelerate progress on their Kyoto, and additional, commitments. The specific targets of the INDCs will not be mentioned, but ideally, the agreement will contain an obligation to “prepare, communicate and implement domestic policies and actions” to reduce emissions in line with targets listed in a common registry.

2. Ratchet-up ambition mechanism

Any agreement will need a framework to increase national commitments over time. This is crucial because we know that the aggregate impact of the INDCs, should they all be achieved, is insufficient to stave off temperature change of 2.7-3.5 degrees. The ambition mechanism should require all parties to review their progress in five-year cycles, with an obligation to increase, strengthen or upscale their ambition. This would start with a review in 2018 to put forward more ambitious 2030 targets. The risk here is that the language will be diluted to “review” targets which provides no guarantee of increasing commitments or prevent the lowering of targets.

3. Long-term goal

Eventually, all countries will need to decarbonise their economies. All short-term goals must lead to this outcome. Countries will need to set out a clear target date for decarbonisation, coupled with a clear reference to the pace of decarbonisation. The negotiations pose two risks to this outcome. First, is that the target date is too late or the pace of decarbonisation is too slow to avoid breaking the carbon budget. Second, is that the language around decarbonisation is weakened to something like “near-zero” or “phase out” or “net zero”, all of which imply continued emissions.

4. Transparency and accountability

As well as committing to cutting emissions, there needs to be some way to ensure countries actually follow through on those commitments. Currently, countries can monitor themselves which has given rise to allegations of tricky accounting, and makes it impossible to assess collective progress. Ideally, the Paris agreement will require all countries to adopt a single, common accounting methodology and set up an independent body to oversee it.

5. Finance

Cutting emissions, adapting to the unavoidable impacts of climate change, and transitioning to renewable energy will cost money. The debate is still raging over who will pay for it. To finance the transition, nations have set a goal of US$100 billion by 2020, and pressure is on to increase this after then. As it stands though, barely a tenth of this has been raised. Historically, only developed countries have been asked to cough up, but they are pushing back on the developing world to put some money on the table. The principle of differentiation is key here–how do we distribute responsibilities differently based on different needs and capabilities? This is likely to be the issue upon which the agreement lives or dies.

6. Adaptation

Given climate change is now an unavoidable reality, countries will need to adapt to a changed climate. This is a key part of the financing push, with some nations calling for half of the $100 billion to be set aside to help countries adapt. This is unlikely to happen, but will probably not be a deal-breaker, even for the most vulnerable nations.

7. Loss and damage

Even the best adaptation efforts cannot prevent some losses and damage–to property, lives, and infrastructure–from climate related events. Given the bulk of climate change was caused by historical emissions from a few countries, there is pressure for those nations to compensate those who suffer the consequences. This is a line in the sand for developed nations though, who will refuse any agreement that includes legal liability or compensation obligations as they see it as writing a blank cheque.

In short, the agreement should commit countries to completely eliminate greenhouse gas emissions as quickly and transparently as possible, fund the transition fairly, and do so while adapting to a changing climate.

There are four ways this could turn out

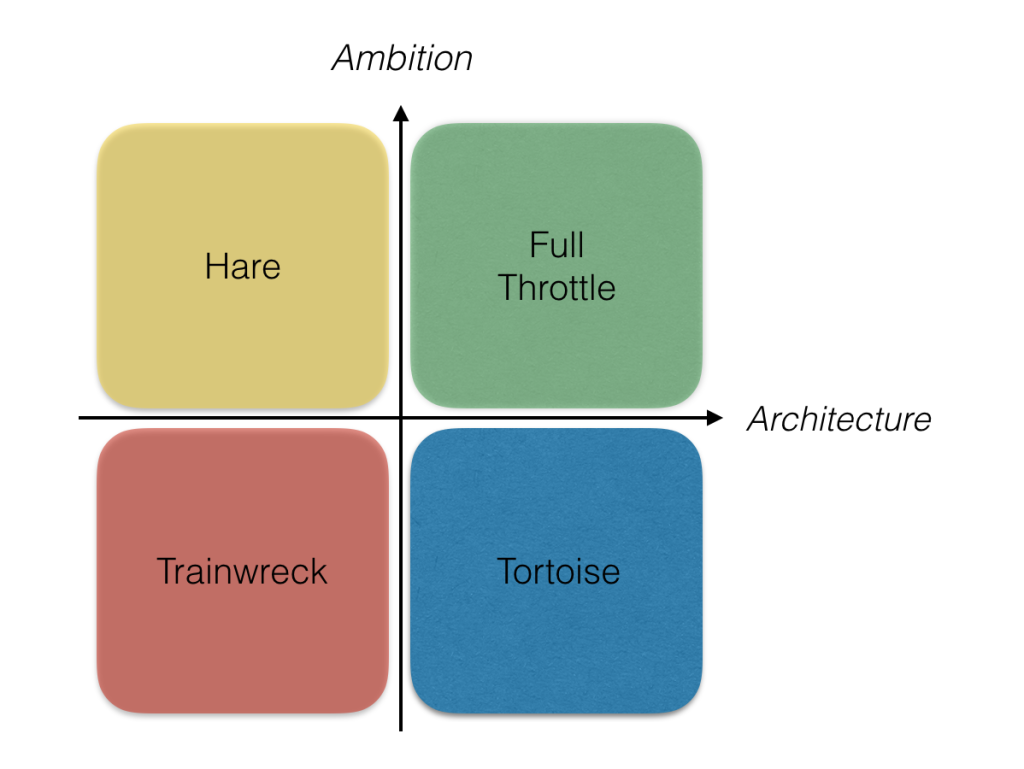

The Compass will follow each of the key issues along our Ambition-Architecture matrix throughout the negotiations. Ultimately, the success of the agreement will depend on how many of the issues end up in the Full Throttle quadrant, and how many end up in Trainwreck. Each of the issues is debated separately, and they are often traded off for each other. As such, as we are likely to get a combination, something in the middle. But broadly speaking, there are four ways things could go.

Full Throttle

High Ambition, Strong Architecture

The core legal agreement contains strong language on all or most key issues, with significant short-term ambition, and clear architecture to scale up in the future. This would be a game-changing accelerator that would put in place a new climate regime capable of driving the world to decarbonisation as soon as possible. A Full Throttle agreement would meet pre-2020 finance targets, a common accounting framework, and a clear ratchet-up mechanism to increase ambitions across all key issues from specified baselines.

The Tortoise

Low Ambition, Strong Architecture

We fail to generate significant immediate ambition, but do succeed in establishing the right architecture to scale up future progress.Under a Tortoise agreement, we will have a path to decarbonisation, but the pace will be too slow to avoid 2℃, requiring a massive future scale up to avoid breaking the carbon budget. This would likely involve several of the key issues, like loss and damage and finance, being excluded from the core legal treaty, or included but with weakened language. A Tortoise agreement would however contain a strong framework for five-year review cycles to scale up commitments for issues like mitigation, adaptation and finance. This would not be a disaster, but would rely heavily on political will over the next 15 years to accelerate progress.

The Hare

High Ambition, Weak Architecture

We secure strong commitment for the short-term but fail to create strong architecture to scale up ambition for the future. This would be a short-term boost, but leave significant questions for the post-2030 period, likely requiring a new agreement to be forged. A Hare agreement would garner strong mitigation commitments, and meet the pre-2020 finance goal of $100b, but this would come at the expense of a ratchet-up mechanism to increase ambition over time, and would fail to secure agreement on a long-term goal. A Hare agreement would be seen as a missed opportunity to establish a new international climate regime, and we could be back negotiating a new agreement in five or 10 years.

The Trainwreck

Low Ambition, Weak Architecture

We get a weak agreement with low ambition until 2030, and no mechanisms to scale up action. This would not help us for either the next decade, nor any decade after that. This would involve weak short-term mitigation commitments, flatlining finance commitments, vague adaptation language, and would see loss and damage excluded from the core agreement. A Trainwreck agreement would invite comparisons to Copenhagen, be widely seen as a failure, and would likely spark another major attempt to forge a new treaty within the next 3-5 years. No country wants this outcome, and a full Trainwreck is unlikely, but if agreement cannot be reached on the key issues, it cannot be ruled out.

comment