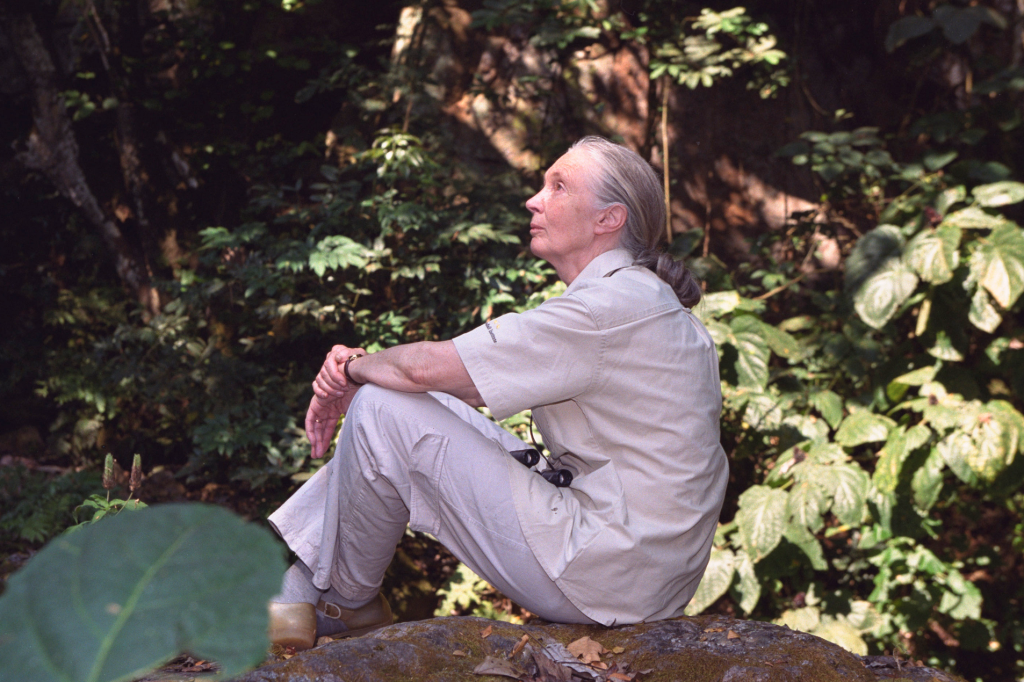

Jane Goodall recently turned 80. The world-renowned primatologist is on a whirlwind tour of the world to share what she’s learned. Dr Goodall is the de facto rockstar grandma of the environmental movement. No exaggeration, she literally defined what it means to be human.

Famous for discovering that chimpanzees also use tools and sometimes eat meat, she spent years in the Tanzanian jungle living with the chimps. She now spends her time with homo sapiens promoting her unique brand of conservationism.

Dr Goodall took time out of her hectic schedule to sit down for a conversation with The Verb to talk activism, inspiration and the future of the Jane Goodall Institute.

Photo credit: Jane Goodall’s Wild Chimpanzees

Lachie McKenzie: I went to Ngorongoro Crater in Tanzania last year and saw all these beautiful animals and I wonder whether in my lifetime we’re going to lose places like this?

Jane Goodall: We could. That’s why I’m travelling 300 days a year. I think the only reason I have hope is because amongst all the doom and gloom there are these bright shining lights. No more will there be drilling for oil in the Virungas [Democratic Republic of Congo] and that’s a big success. But it doesn’t mean it’s safe forever. It’s like somebody being shown they are free of cancer: it hangs over you for the rest of your life. So whether there will ever be a time we can be complacent I don’t know. But so many of our young Roots and Shoots people have been through the program and their voices are being heard. You see these signs of hope coming from China like banning shark fin soup. There are signs of change and that’s all the more reason to push harder and make the most of it.

Why is World Heritage so important?

There have been some World Heritage sites destroyed. I think it’s like having a law for animal protection. It doesn’t mean it’s going to protect all animals, but it’s a starting point and a recognition that this should be done. There are always ways to get around everything. At the moment it’s money that’s counting. Money and the lobbying power of the big multinationals and that along with corruption are the two most vital things to fight – and I don’t know how to fight them.

You have the natural advantage of World Heritage areas being more beautiful than coal mines.

The coal mine has about 30 productive years, whereas if it’s kept as World Heritage and the right kind of ecotourism is developed it will last for centuries. Also, the effect of coal mining can last for thousands of years and the number of farmers whose businesses will be destroyed is staggering.

Speaking of economics, what do you think are the main barriers to a globally binding treaty on climate change ahead of Paris in 2015?

I was just talking to the advisor to the president [Laurence Tubiana] in Paris who is pulling together this conference and we decided it was important to have a youth component there.

Do I think there will be a legally binding agreement there? I’d be very surprised.

The two great carbon sinks are tropical forests and the oceans, and we know that in both cases their ability to be the lungs of the world are being horribly compromised. I don’t know enough about the success of some of these emissions capping projects, but I know they’ve been successful in Costa Rica. We’re doing pilot study for REDD+ in Tanzania and we’re using the same methods as we used with the people around Gombi National Park.

On the ground I don’t think it’s that difficult to protect the land. You just have to work with the people and do something to alleviate crippling poverty. If we have poor people living around any wilderness area then it’s not going to work. This is the problem in India. But I think that more people are understanding that climate changes does pose a huge problem; a political problem, as well as a problem for the UN. It comes back to the power of the big corporations, the old boys network, the huge power of agribusiness, the pharma industry, oil and gas, the timber industry and the arms manufacturers.

In a democracy, if you don’t like what your leaders are doing then don’t elect them, but I don’t think there are many democracies left honestly. It’s not clear we have a democracy.

It depends on what they’re protesting about.

That’s where my job comes in.

Does the Jane Goodall Institute’s Roots and Shoots program deal primarily with young people?

Well, preschool all the way through university, so that’s not so young. The last group we formed is currently at the World Bank in Washington D.C.

Do you see the same enthusiasm you have for conservation reflected in people involved in your programs?

Absolutely. My biggest hope is going around the young people and seeing not just their enthusiasm, but their gritty determination. They know we’re running out of time.

Would you describe yourself as a conservative, a radical or somewhere in between?

In between. My mother taught me to listen to the people on the other side. Because sometimes you can compromise. As long as you don’t compromise your values. I believe progress is a series of compromises.

What’s next for the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI)?

To develop the global structure. We now have JGI Global and it needs money. It has 28 chapters, but the bank account has US$1,000 in it. We also have a board. You can’t get money until you are ready, but we are ready now to grow and to get some corporations involved.

What kind of corporations have you been courting?

We haven’t really courted any yet because we’ve only just got our house in order. Some companies I’m not too keen on have been approaching us.

Are you worried about greenwashing?

Yes, that’s the problem so we haven’t taken huge amounts of money from any corporation that could use us for greenwashing. Sometimes when you work with a corporation that’s trying to do it right, you can help them do it better.

What else are you passionate about?

Meat eating. People don’t realise it causes harm.

What about people who love meat, what would you recommend to them?

First of all people should eat less meat. I’m not advocating people go vegan. I’m not extreme. I’ve been successful in getting people to say ‘I will eat less meat.’

Also getting people to become vegetarian, even in Argentina where they seem to only eat beef. That’s why I carry Cow [a stuffed toy], who is my spokesperson for abused farm animals.

Huge areas of forest are destroyed every year to grow the grain to feed cows. Huge areas of habitat are destroyed by free grazing cattle and goats and sheep. Cows produce methane gas, which is even worse than carbon dioxide. We’ve also got the fact that to keep these animals alive in these horrible factory farms, there is misuse of antibiotics. Bacteria are building up resistance all the time. There is absolute agreement that one of the main reasons of this building up of resistance is the meat industry.

When I left the UK there was a headline saying ‘The Era of the Antibiotic is Over.’ I was talking to the director of the National Institute of Health and he was saying much the same thing. Think what that would mean if it’s true. It’s not pretty. Populations are levelling off. What would happen if we can’t have antibiotics? I suppose if we were aliens coming in from Mars we’d say something has to happen because there are too many people.

Alleviating poverty can help, too.

It does. The program we have around Gombi, Tanzania is a blueprint for USAID to give their aid. You work with people in a very holistic way. They get to choose, and they chose food, reclaiming farm land, better education and better health. You must introduce family planning, which is accepted if you go about it the right way and you don’t talk about population control. So we provide family planning information. We try and get girls to stay in school with scholarships and sanitary supplies and toilet doors that lock. Family size decreases as women’s education improves.

We also do microcredit for projects that are environmentally sustainable. In Gombi we are reclaiming forests in 52 villages. They’ve set village land aside and within 30 years there are more trees, so the chimps have more forest and now they have corridors. This is true in Uganda, DR Congo, Congo Brazzaville and Senegal.

JGI seems to be focussed on direct projects rather than lobbying governments.

I think you can lobby governments better when you actually have something proven to work. I do talk to various senators and congressmen in the US and I met with the Minister for Environment in Australia and he was very receptive to JGI participating in the forestry discussions in Australia. You seize at straws, you try and you never know.

Where are you off to next?

Bali and then New Zealand. Then NZ, then Nepal, then Tanzania, Kenya and Burundi.

You must enjoy all the travel?

I hate it. I absolutely hate it. Everywhere I go obviously there are groups of people I really like, but the travel, the airports, the hotels, lectures and interviews.

It’s hard being an activist.

And it’s been since October 1986. It’s mad isn’t it?

It doesn’t seem to be tiring you out too much though…

Well everyone says I’ll burn out, but I can’t burn out, I spend too much time with the youth. On the one hand it’s desperation and on the other hand we cannot fail to give children hope.

The Australian Government always talks about not leaving a burden to the next generation, but they mean national debt, and so they generally just cut welfare programs, but they don’t talk so much about the mess we are leaving to future generations.

No, they do, but they say it’s their responsibility. Well, it’s ours.

They say we don’t inherit the planet from our parents, we borrowed it from our children, but we’ve stolen it. Gandhi said the planet can provide enough for human need but not human greed.

Dr Jane Goodall, thank you.

It’s been a pleasure.

For more, see this National Geographic video.

comment